Back in early March, shortly after I revived this blog, I wrote something called, “Why now, and why here (Part 1)”. I talked about why I chose Amsterdam for this adventure of ours. I spoke about the connection I’ve long felt with the Dutch, and the reasons, both practical and silly, that brought me here. That covered the “why here”. As for the “why now”, I sort of cryptically deflected it for another time.

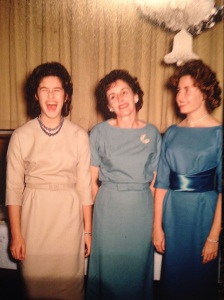

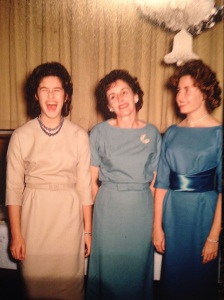

Wedding day, May 2004

What I was skirting around was having to connect our move to the death of my mother on August 5, 2014. Maybe I wasn’t ready to make the connection, or to talk about it in a public space. To be fair, one didn’t directly lead to the other. I had been talking about moving abroad for some time, and my mother was supportive and excited for us, encouraging us to make our plans regardless of her health.

They say that you’re not supposed to make any big life decisions in the year after a significant loss. Well, I blew that one. Instead of following the common wisdom, I took off, alone at first, to a place where I had no community, no support. I also had no triggers; my mother had never been here and there was little to remind me of her.

Maybe I was trying to outrun my grief. Maybe, in the face of loss and the regret that inevitably comes with it, I felt a greater urgency to do something that I had always dreamed of doing – no time to waste. I’ll admit I haven’t really given it much thought. There’s time to figure it out, if I’m so inclined: “grief is real and loss is for life, as long as life.“ In any case, I’m not sure it matters.

What follows is a bit of patchwork (an analogy my mom would have appreciated) written inconsistently over the past year. Although I’ve tried to piece it together in a way that might make sense, it is, like all handmade things, imperfect.

I’m sending this out, with great love and childish hope, to my mom and all those we love but no longer see.

On the day my mom died, a friend who had recently lost her mother sent me an email. In it, she shared a quote from an essay that Laurie Anderson wrote for Rolling Stone about the death of Lou Reed, her partner of more than 20 years. It said simply, “I believe that the purpose of death is the release of love.”

(I think it’s important to point out here that my mother wouldn’t have had the slightest idea who Lou Reed was, to say nothing of Laurie Anderson. Her musical tastes ran more to Lionel Ritchie and the Bee-Gees. But hey, nobody’s perfect.)

Women in waders. Fly fishing in North Carolina, May 2010

This single sentence from Anderson’s beautiful reflection was like a life buoy thrown to me just as the sea was rising. My mom had been sick for a long time, and as her health declined we had the frank, tearful conversations that I imagine most families have in these situations. Still, the knowledge of her illness and her worsening condition remained abstract, almost up to the very moment of her death. How can we ever prepare ourselves for such loss?

There are parts of that day and the days that followed that have blurred. Even in grief – perhaps especially in grief – our brains find ways of protecting us from ourselves. Other parts of the day are crystal-clear; I could close my eyes right now and reconstruct every sensation, if not for the fact that it still hurts so much to do it.

What I both remember and find comfort in reliving is the outpouring of support that my mom’s death inspired. One after the other, friends, neighbors, former students, quilters, and teachers shared memories. Remarkably, almost everyone remembered the first time they met my mother. There was story after story of her suggesting that someone join a parent’s group, or take a sewing class, or contribute to a gift for a retiring teacher. Stories of invitation, of welcome, of encouraging someone to do more than they thought they could.

Of course, what she was really doing was inviting people into the circle of her love.

Life inside that circle was remarkable. My mom was generous with her time and her attention. She knew how to listen. She was creative and artistic. Affectionate. Curious. She was a loyal friend who would go well out of her way for others. She did not give up on people. She sacrificed – or at least delayed – her own ambitions in order to care for her family.

The Budapest stop of our European adventure, October 2012

This is not to say that life inside the circle was always easy. While the circle of love may not have had conditions, it did have – how shall we say? – standards. There was a way that things were to be done, and this was non-negotiable. My mother had high expectations for those around her. To do a poor job on a school assignment, for example, would be disrespectful to ourselves and to the teacher who assigned the work. Whether it was homework or household chores, there was no greater sin inside the circle than doing a “half-assed job”.

And the flip side of my mother’s fierce loyalty was that she could hold a grudge like no other. I suspect she went to her grave still angry at my high-school boyfriend for breaking up with me. In 1993.

I’ll pause here to say that trying to explain the heart of who my mother was in a few paragraphs is a fool’s errand – the ultimate half-assed job. If you knew her, you’ll know that nothing I can say will properly capture her. Edna St. Vincent Millay gets it right in her poem Dirge Without Music:

“A fragment of what you felt, of what you knew,

A formula, a phrase remains,—but the best is lost.

The answers quick and keen, the honest look, the laughter, the

love,—

They are gone.”

I’m not sure that there is a purpose to death at all, but I’m willing to entertain the thought that the purpose is, perhaps, the release of love. And I’ll consider it only because in the days following my mother’s death, I felt held and lifted and comforted by the love that came back from the circle she had created over so many years. My mother had stepped out of the circle. And so we all had to move that much closer to each other. And it was her love that allowed us do it.

God, my mom would have hated this picture. I love it. Unknown location and date.

In a wonderfully honest new book of essays, Meghan Daum writes, “Most of us have unconscious disbeliefs about our lives, facts that we accept at face value but that still cause us to gasp just a little when they pass through our minds at certain angles.” The first thing on her list is the same as mine: that my mother is dead. A year has passed and this fact seems no more believable today than it did on the day of her death. My most common thought in the first few days of her absence was a befuddled, “…but she was just right here…”. As one might remark about a missing set of house keys.

That thought has by now largely passed, but I’m not sure what’s taken its place. I can say that everything about this year has been surprising. Nothing is linear. Progression is followed by regression. The fact that I moved to Europe a mere six months after my mother’s death has no doubt made the grieving process more complicated. In the early weeks after my arrival, loneliness was common. I was fine for long stretches, then found myself ambushed by grief, unable to share or manage it.

I was – am? – vulnerable in ways I could not have anticipated. And what you cannot anticipate or imagine, you cannot defend against. I have done things that are selfish and thoughtless and inexcusable, even when viewed through a generous lens of grief. I’ve had moments where I was unrecognizable to myself. And while some of those moments are shameful to me, and hurtful to others, I honestly don’t think I could have expected my heart to have protected me, broken as it was.

And the love that I want to believe was released in that hospital room? The love that closed around those of us left in the ragged circle in the days after my mom’s death? What of that? What happens to it in the months – years? – after its release? Will it become harder to call to mind, harder to feel? Does it become diffuse, stretching to reach everyone as they need it, each in their turn? Or can it continue to grow, to expand, both for and through those my mother loved, and who loved her? Could it be that it is endless? Could it be so?