September is a busy month, and there’s a lot I could share. Like our recent trip to the U.S., a new educational program I’m starting soon, or the Amsterdam canal tour en francais that I won last night. But for the last few weeks, I’ve been thinking about space. Not square footage – I’m talking about the universe. Fair warning: if this is of no interest to you, or if you think that space exploration is a waste, you may want to stop reading now, because there’s a lot of space stuff to follow…

I’m a bit of a space geek, which in recent years I credit to Chris Hadfield, the Canadian astronaut and former Commander of the International Space Station. He is a true Renaissance man: a musician, an author and speaker, a fighter pilot, and a professor. (He also has an airport, two schools, and an asteroid named after him.) I started following him on Twitter when he was still at the ISS, sending photos back to earth, making science and space travel both exciting and accessible.

Then, while I was stocking up on e-books for our trip to America, I found the wonderful “Leaving Orbit: Notes from the Last Days of American Spaceflight” by Margaret Lazarus Dean. Dean is a professional reporter and novelist, and an amateur space junkie. She made it her mission to document the last flights of the space shuttle program. She writes with a mix of wonderment and sadness, grateful for having witnessed the later stage of space travel, but mourning the loss of the national vision and individual courage that brought Americans to the moon. It was a captivating read, in part because Dean is roughly my age, and her memories of the Challenger disaster tracked so closely with mine. The book helped me understand the significance of the Challenger explosion. It shook America’s confidence in NASA and contributed to the end of the shuttle program, but it also communicated a profound message to the many students who had watched the explosion happen on television. Writing about the report of the investigation of the explosion, Dean explains that the failures it catalogued were not surprising to young people: “We had already come to realize that the adults in charge of making the world run smoothly actually had no idea what they were doing”.

But wait! There’s more. This year marked the 40th anniversary of the launch of Voyager 1 and 2, and if you have the slightest interest in this amazing project, go watch The Farthest. The PBS documentary features the women and men who have spent their careers tracking and translating the images that the Voyager satellites send back to earth. The ambitious “Grand Tour” of the outer planets revealed moons, massive storms, plumes and craters, giving us a glimpse of our solar system and beyond. And if that’s not interesting enough for you, both Voyager satellites carry a golden record with messages in over 60 languages, music, natural sounds, and data that an advanced civilization could convert into diagrams – a global greeting card from earth.

Jupiter Great Red Spot (Photo credit: NASA/JPL).

Just four years ago, on 12 September 2013, Voyager 1 passed into interstellar space, and became the first man-made object to do so. What I remember most about this event is the pleasure of adding the word “heliosphere” to my vocabulary. The Voyager satellites are expected to send data back to earth for another 3-7 years, and then they will continue to travel, silently, long after there is anyone left who remembers them.

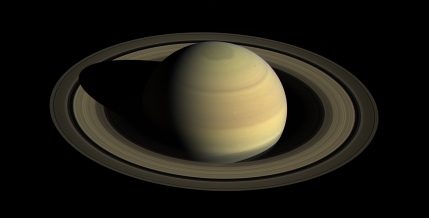

Then there is Cassini. In about 15 hours from now, Cassini will end its 20-year journey in dramatic fashion. The NASA website says it best: “Having expended almost every bit of the rocket propellant it carried to Saturn, operators are deliberately plunging Cassini

Saturn, Approaching Northern Summer (Photo credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

into the planet.” In anticipation of this end, Cassini began doing a series of dives several months ago, passing between Saturn and it’s rings. Tomorrow’s Grand Finale will see Cassini make a final approach to Saturn, dive into the atmosphere, and eventually burn up.

Now that you’ve put up with all this space talk, I have to admit that it’s not the “how” of space travel that interests me – much of the science is well beyond my understanding – but the “why” of it. The “how” is mostly about the technical questions: Will it work? For how long? Are our calculations and assumptions correct? Will we get any data back? What can we learn? Once those are resolved, the “why” follows: What will we find? What are we hoping for? Are we prepared for what we might discover?

Many of the people working on space projects do so with the understanding that their project may not get off the ground. And if it does get into orbit, if it goes as planned, they may never see how it ends, as with Voyager. Or they may, in the case of Cassini, purposely and beautifully engineer the destruction of their spacecraft. These possibilities – or more accurately, the acceptance of these possibilities – fascinate me. It’s the legacy of the first astronauts, those brilliant and handsome young fighter pilots who took on an impossible challenge, some later admitting that they thought the odds of survival were, at best, 50/50. They accepted risk and uncertainty because it paled in comparison to the magnitude of what they might accomplish: going to space.

So if you’ve read this far, you should really head over to the NASA image library, or learn about the Cassini team’s tradition of Friday breakfast, or get to know the three new crew members who arrived at the International Space Station just two days ago. And I’ll sit here a little longer and marvel at the fact of space travel and the wonder of it all. That, as Margaret Lazarus Dean put it, “completely normal-looking middle-age people are currently floating in space somewhere overhead. There is simply no getting used to this.”